Feynman Technique for Learning: Reading as an Approved Tool for Deep Learning

- kutu booku

- Dec 12, 2025

- 10 min read

A neuroscience-driven essay on how reading cultivates the mental habits that shaped one of history’s clearest thinkers

Richard Feynman had an unusual approach to knowledge. He did not aim to “store” ideas the way many learners do. He aimed to rebuild them. His mind behaved less like a warehouse of facts and more like a workshop of active, shifting models — constantly reconstructed, tested, and simplified.

Research from Boston Children's Hospital and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development has supported studies on brain development, child health, and human development, highlighting how reading books can rewire the brain, strengthen neural networks, and enhance communication between brain hemispheres, especially in young children.

What’s remarkable is that reading trains young brains to operate in this exact workshop mode, even if the child has never heard of Feynman or set foot in a physics classroom. Reading doesn’t just give children access to information; it shapes the very architecture of how they think. In fact, one study found that regular reading for pleasure in childhood is associated with measurable improvements in brain structure and function, supporting the idea that reading can directly influence cognitive development. Reading books to young children in early childhood supports brain development, brain health, and good brain health, and is linked to better academic achievement and mental health outcomes.

This is where the connection between Feynman and reading becomes powerful — not because Feynman was a reader (he was), but because the cognitive demands of reading naturally mirror the mechanisms that make deep understanding possible. Reading books exposes children to over a million words before they enter kindergarten, which supports language development and phonological awareness. These findings have important implications for education and child development, suggesting that encouraging reading can play a key role in fostering deep learning and critical thinking skills.

And unlike worksheets or structured lessons, reading does this in a quiet, internally driven way that aligns beautifully with how the developing brain prefers to learn. Recent research in neuroscience further reinforces that reading not only supports language acquisition but also strengthens neural pathways involved in reasoning, memory, and emotional intelligence. Reading strengthens white matter and supports brain maturation, with developmental changes observed in the same regions of the adolescent brain.

Reading books helps reduce stress levels, supports mental health, and improves quality of life, not just for children but also for elderly patients, by maintaining cognitive function and neural health.

Parents are encouraged to read books with their children regardless of socioeconomic status, as this strengthens the parent-child bond and supports cognitive and emotional development.

While video content can introduce topics quickly, what truly matters is the act of reading itself for brain health and development, as reading provides depth and comprehensive understanding that video content often lacks.

For example, reading books supports phonological processing, activates Broca's area, and leads to better readers and higher scores in language and cognitive assessments.

Reading Forces the Brain to Build a World, Not Memorise One

Feynman believed knowledge had to be reconstructed, not repeated. Reading requires this reconstruction constantly. When children begin reading, they engage cognitive processes that are foundational for learning, activating areas of the brain that support language, memory, and comprehension.

When a child reads, their brain is not copying a story. It is:

building a scene from text

allocating attention to narrative cues

constructing causal chains (“This happened because…”)

tracking motivation (“She did this because she felt…”)

simulating possibilities (“What if he chooses differently?”)

strengthening neural pathways and supporting phonological awareness, which are essential for reading accuracy and fluency

These processes occur even before a child can articulate them. And unlike learning activities that present images or videos, reading provides bare scaffolds — text fragments that the brain must animate internally. When reading, the brain processes visual information differently than when viewing images or videos; instead of receiving direct visual input, the occipital lobe must generate mental imagery from the text, stimulating imagination and creative thinking. While video content can introduce topics quickly, it often lacks the depth and comprehensive understanding that reading offers. What truly matters is the act of reading itself, as it is crucial for cognitive development and long-term learning benefits.

This engages a set of cognitive functions that were central to Feynman’s own style of thinking:

internal simulation

coherence building

checking assumptions

updating mental models

For example, parents can support children as they begin reading by asking questions about the story, encouraging them to predict what might happen next, or relating the story to their own experiences. This kind of parental involvement not only fosters literacy but also strengthens emotional bonds and helps children develop critical thinking skills from an early age.

Reading is not passive intake. It is the brain constructing reality from clues — a deeply Feynman-like operation.

The Feynman Habit: Turning Language Into Structure

Feynman’s notebooks, now iconic, reveal a striking pattern: he translated ideas into entirely new structures — diagrams, analogies, invented examples, verbal reconstructions.

Children do something similar without instruction when they read. They convert vague textual input into:

mental maps of events

categorisations of characters

temporal sequences of actions

thematic groupings of ideas

Reading strengthens cognitive skills such as phonological processing, which is essential for decoding and understanding text.

These structural transformations involve the frontoparietal network, a region responsible for relational thinking — the ability to understand how concepts connect. Multiple brain regions work together to support the structural thinking skills developed through reading.

For example, parents can help children develop structural thinking by reading a story together and then asking the child to map out the sequence of events or categorize the characters, turning reading into an interactive learning experience.

Unlike previous articles, which emphasised memory or metacognition, here the focus is on something different:

Reading cultivates structural thinking — the brain’s ability to rearrange ideas into meaningful forms.

This is the skill that made Feynman unusually gifted.

Not recall.

Not cleverness.

But structural clarity — something reading quietly trains in every child.

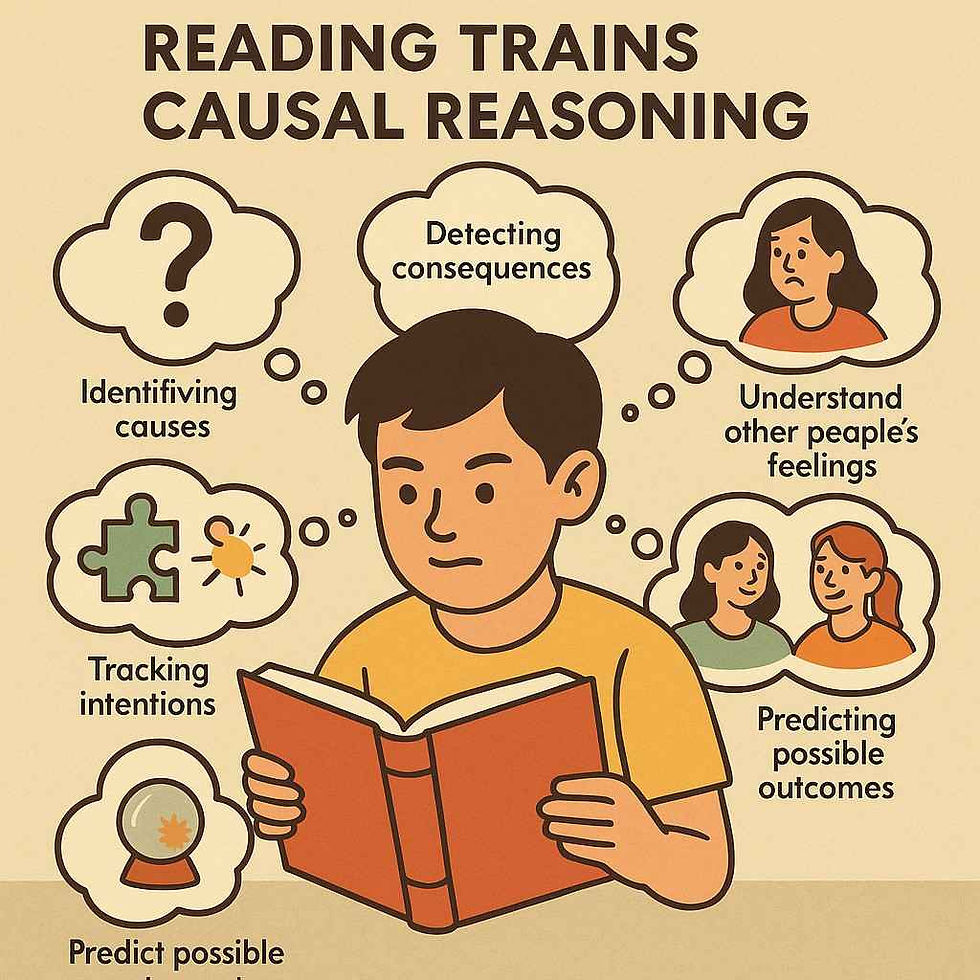

When Reading Trains Causal Reasoning

Causal reasoning is a core part of Feynman’s intellectual signature. He didn’t want to know what happened, but why.

Reading develops this far earlier than formal schooling expects.

Every narrative — even the simplest one — demands:

identifying causes

detecting consequences

tracking intentions

predicting possible outcomes

interpreting emotional shifts

understanding other people's feelings

Videos make this work easier because the causal cues are explicit. Reading, by contrast, hides those cues inside language.

This is cognitively demanding in a way Feynman would have admired: the child must actively extract causality rather than receive it.

This extraction strengthens networks tied to:

scientific reasoning

moral understanding, as well as the ability to relate to people's feelings and develop empathy for other people's feelings,

decision-making

prediction under uncertainty

Reading is a child’s earliest laboratory for causality — long before science class begins.

Reading Trains the Brain to Tolerate Ambiguity — A Signature Feynman Trait

One of the least discussed aspects of Feynman’s mind was his comfort with ambiguity.

He often sat with incomplete data, unclear rules, or conceptual contradictions long before arriving at an answer.

Reading develops this capacity quietly.

Stories do not give the whole picture at once.

They unfold slowly, withholding information and revealing motives gradually.

Children must endure ambiguity such as:

What is the character really trying to do?

Why is this conflict happening?

Is this narrator trustworthy?

What is the theme connecting these events?

This strengthens the anterior cingulate cortex, a region involved in conflict monitoring and the regulation of uncertainty.

In simpler terms:

Children who read become children who can think without needing immediate clarity.

This ability — to think in uncertainty — was one of Feynman's great cognitive superpowers.

Reading + Openness Equals Cognitive Expansion

Feynman was allergically allergic to intellectual rigidity. He approached ideas with curiosity rather than defensiveness.

Reading introduces children to:

unfamiliar perspectives

new emotional worlds

contradictory viewpoints

alternative solutions

cultures unlike their own

This exposure enhances their communication skills and language skills, helping them express ideas clearly, understand others, and build strong literacy from a young age. Reading strengthens empathy and flexible thinking by allowing children to see the world through different eyes and adapt to new ideas.

For example, parents can support openness by reading stories with their children that feature characters from diverse backgrounds, then discussing how those characters feel and make decisions. This helps children relate to others and become more accepting of differences.

This stretches the default mode network, which governs:

imagination

empathy

flexible perspective-taking

Reading also contributes to developmental changes in the brain, supporting the growth of neural pathways involved in empathy, imagination, and social understanding.

A rich reading experience also fosters empathy and flexible thinking by exposing children to diverse language patterns, stories, and viewpoints.

In earlier articles, we explored metacognition and memory. Here the focus is different:

Reading expands the self by expanding the mind’s models of other minds.

This is not only a literary skill; it is a cognitive one.

And it is profoundly aligned with how Feynman approached the world — with openness rather than certainty.

Reading as a Low-Pressure Cognitive Gym

Unlike structured lessons, reading operates without immediate evaluation. Nobody checks a child’s “reading explanation score.” This low-pressure environment induces:

longer sustained attention

deep engagement cycles

intrinsic motivation loops

Reading in such an environment can help reduce stress and stress levels, promoting emotional well-being and relaxation. Scientific studies show that reading not only helps reduce stress levels but also supports mental health throughout life, including for elderly patients who benefit from improved cognitive function and emotional well-being.

These states promote synaptic consolidation — the strengthening of neural pathways associated with comprehension and reasoning. Regular reading also supports brain health by enhancing neural development and maintaining cognitive function.

Feynman thrived in self-directed environments. Reading offers children the same psychological conditions: a space where thinking feels like exploration, not performance.

This supportive environment can help lower stress levels and support overall emotional well-being. Parents play a crucial role in creating and maintaining this supportive reading environment, fostering positive reading habits and supporting their child's language, emotional, and cognitive growth throughout life.

FAQs

1. Why is reading such an effective tool for developing Feynman-style thinking?

Because reading requires the brain to internally construct, test, and refine meaning — the exact learning loop Feynman used consciously. For example, when children begin reading books, they often ask questions and discuss what they read, which mirrors the Feynman technique of breaking down concepts and explaining them simply. Parents play a crucial role in this process by reading books with their children, encouraging questions, and fostering conversations that help develop Feynman-style thinking. Books demand reconstruction rather than memorisation, engaging neural systems tied to inference, modelling, and conceptual clarity. What truly matters is the act of reading and engaging with books, as this process significantly enhances reading comprehension, enabling learners to deeply understand and retain information rather than just recall facts.

2. How does reading strengthen reasoning and scientific thinking?

Reading helps children develop reasoning and scientific thinking skills by engaging their minds in identifying causes, detecting patterns, making predictions, and revising assumptions. Reading strengthens reasoning skills and supports phonological processing, both of which are essential for cognitive growth. These skills are closely linked to academic achievement and often result in higher scores on cognitive and language assessments. Stories require children to use these same cognitive skills, which are foundational for scientific reasoning, long before formal science education begins. Additionally, reading contributes to developmental changes in the brain, supporting the maturation of neural pathways involved in literacy and learning.

3. My child reads but doesn’t explain much. Is that a problem?

Not at all. Explanation is a secondary skill that can be nurtured gently. What matters first is that the child is processing — building internal models. For example, some children are internal processors and may not readily share their thoughts aloud; parents can support them by reading together and then giving them time to reflect before gently inviting them to share, perhaps through drawing or storytelling. With time, reflective questions (“Why do you think…?”) help externalise those models. Parents play a key role in encouraging discussion and reflection, which helps children articulate their thoughts and deepen their understanding. Additionally, discussing books with others can further support this process by encouraging children to articulate their thoughts and deepen their understanding.

4. How does reading help develop cognitive flexibility?

Every genre, narrative structure, and character perspective requires a shift in thinking style. These shifts strengthen the frontoparietal network, which underlies adaptability, creativity, and problem-solving. Reading also strengthens working memory, which supports cognitive flexibility by helping children hold and manipulate information as they encounter new ideas and perspectives. Additionally, reading strengthens cognitive flexibility and supports developmental changes in the brain, fostering neural growth and adaptability essential for lifelong learning.

5. Why does reading build comfort with ambiguity?

Stories rarely present complete information upfront. The child must hold unanswered questions, tolerate incomplete knowledge, and revise assumptions. This strengthens neural circuits responsible for managing uncertainty. Reading in such ambiguous situations can also induce an altered state of deep focus and immersion, where the child becomes fully absorbed in the story, promoting relaxation and mental engagement.

6. Does re-reading the same book still promote Feynman-like thinking?

Absolutely. Re-reading is not repetition — it is refinement. Each pass reveals new causal links, emotional cues, and thematic patterns, deepening the child’s internal model of the story. Re-reading also exposes children to a million words, supporting vocabulary development and literacy skills. This practice helps children become better readers by reinforcing language skills and supporting brain development associated with reading. Parents play a crucial role in encouraging re-reading, fostering positive reading habits and supporting their child's growth as a reader.

7. How does this differ from the roles of memory or metacognition covered in earlier articles?

Unlike earlier pieces that emphasised how the mind monitors itself or stores information, this article focuses on the structural, causal, and modelling capacities that reading develops — the precise skills that made Feynman’s mind so agile. For example, reading books with children can help them understand how events are connected, why characters make certain choices, and how one action leads to another, thereby developing their structural and causal reasoning skills. These are core reading skills that go beyond simple memorization. What truly matters is the act of reading and engaging with books, as this process supports cognitive, emotional, and developmental growth regardless of the language or medium.

Explore our Kutubooku Book Boxes, curated by reading specialists to turn every story into an adventure in imagination and growth.

Have questions about your child’s reading journey?

connect with our experts — we’ll help you choose books that match your child’s age, interests, and stage of development.

Comments